Something in the Water

Story by Chris Landers

Photos by Christopher Meyers

In 1899, the crew of the ship Endeavor undertook a survey of the Baltimore Harbor as a part of an overall survey of U.S. coastal waters. In his report, Charles Yates wrote that “the bottom of Baltimore Harbor in general seems to be composed of a soft black mud or slime. It is especially soft and nasty about the wharves.”

David Tebera says it hasn’t changed much since then.

“There’s a channel that runs where the main ships come in,” he explains. “There’s a slow slope out to the channel, where it’s rather deep. The closer you are to the channel, the less muck you have. If you’re in by where the boats are, the piers and whatnot, then it can be pretty thick . . . You can kind of reach your hand in and it’s kind of like going through chocolate.”

“It’s not like a solid,” he says. “You just get your hand going in, going in, going in, and it kinda gets stuck in there.”

Tebera is one of the few people to have seen the undisturbed bottom of the Baltimore Harbor, although “seen” may not be the right word.

“Early in the summer, like now,” he says, “if you want to know what the bottom of the harbor looks like, I’m going to say no one can see it. It’s pitch black. You go down 10 feet and it’s complete darkness without a light. Even with a light, then you’re only seeing about 4 inches, or whatever the clarity is at that point . . . . Think of [the bottom] as a fruit cake, or one of those Christmas pound cakes–there’s like an icing along the top, a layer of sediment. You wouldn’t see the bottles and stuff because of the sediment over top, but if you kick stuff up, then you can find a lot. But then you can’t see at all.”

In the colder months, Tebera says visibility can be as much as seven or eight feet. He hopes soon to have an underwater camera working, dragging below the kayak to view images of the harbor floor below, in the past he has had to rely on what little he could see, and his sense of touch through thick gloves. He is predominately a free diver, relying on his ability to hold his breath, something he says he can do for around two minutes, closer to three if he’s been training.

“You find big tarps that have blown off ships, fire extinguishers, big collections of beer bottles,” he says. “I wouldn’t say I find anything I would hang on my wall. The neatest thing I think is in the late fall, when the jellyfish come in, and you’ll be swimming along and they’ll be bouncing off you.”

Some people think Tebera is a bit of a nut, and it’s a reaction he enjoys. He realizes that not everyone would go diving in the Baltimore Harbor, at least not without a good reason. Sometimes, he does have a good reason–retrieving dropped items, like a boat motor dropped by a worker at one of the Inner Harbor paddleboat stands. When Tebera arrived, a float indicated about where the motor was believed to rest, a position fixed by dragging an anchor along the bottom until it struck something. Tebera followed the line down into the darkness, feeling his way around. When he surfaced, he had interesting news: “This isn’t a motor, this is a paddle boat.”

“When I was down there that day,” he says, “I found construction cones, street signs, balls, anything and everything that people could throw in. There’s a lot of bikes–people stealing bikes they’ll just run into the water.”

Tebera isn’t a professional diver, but it is something he has been doing since he was 12–mostly free diving, but he is SCUBA certified as well. In the basin of the Inner Harbor, where the water is little more than 25 feet deep, he doesn’t need his equipment, although he will use breathing tanks when he is near the piers and edges–the water there can go for some distance under the edges of the brick promenade, and in the darkness it is too easy to come up in the wrong place. Before he goes in, he fills his wetsuit with bottled water, in hopes of keeping out the harbor, but he is quick to point out that he has never suffered any ill effects from his hobby.

Tebera sometimes charges for his services–usually around $100–and occasionally, he says, someone will tell him that’s a lot of money for just jumping into the water and retrieving something. “They don’t realize that I stink for two days after,” he says.

The first person to see the bottom of the Harbor clearly was most likely Simon Lake–the inventor of the Lake Submarine, which he tested in 1898. In January of that year, The Baltimore Sun reported a test of the boat, complete with a phone call to Sun offices through a line dropped into the water at South Street. Lake’s Argonaut was a cigar-shaped craft, with wheels for traveling along the bottom and pipes running to the surface for air and to vent the exhaust from a gasoline engine. One of Lake’s innovations allowed a door to be opened in the bottom of the sub.

In an article for The Strand in 1898, writer Henry Hale describes a trip with Lake aboard the Argonaut: “The light through the thick glass bull’s eye window becomes fainter and fainter, and electric light takes the place of the daylight which is being gradually shut out. You feel, indeed, as if cut off from all around the world.”

For Tebera, the silence of the water is a draw. Broken only by the sounds of boats, or the prop wash of tug boats pushing rocks along the bottom, it’s a refuge from his East Baltimore neighborhood. He points to his truck, saying that he’s just come from getting a tire replaced after it was slashed outside his house. He didn’t care for Baltimore when he came here for work a few years ago. Since he started diving, though, he has discovered a different world.

“I love it.” He says. “I go down and you’re there by yourself. For me it’s relaxing. For other people, it’s claustrophobic. My sister’s a diver and she gave it up real quick because she couldn’t handle it. I find it’s one of the greatest things in the world.”

Matt Steinmeier is leaning over the side of the small boat idling in the mouth of the Jones Falls River between the Pier Six amphitheater and the Eastern Avenue Pumping Station when a man walking along the promenade shouts, “Hey! Are you testing the water?

“Everybody already knows we got the baddest water in the world,” the man informs Steinmeier. “I’d rather drink water from a Cambodian river than this water.”

As his wife, Eliza Steinmeier, pilots the boat back into the northwest branch of the Patapsco River, Matt bags the water sample, labeled with the time, date, and location it was collected. He’s helping out today, filling in for a staff member who cancelled. For Eliza Steinmeier, this is a full-time job. She founded the non-profit Baltimore Harbor Waterkeeper, inspired by the Riverkeeper program begun on New York’s Hudson River. She took part in a Riverkeeper offshoot in California while in law school, but there are now similar groups all over the world under the umbrella of an organization called the Waterkeeper Alliance. They monitor the state of the water, but like Eliza, who is an environmental lawyer, they also try to improve it by suing polluters on behalf of the public.

“Baddest water in the world,” Matt says. “We should’ve just consulted with that guy. We wouldn’t have to do all this testing.” Chuckling a bit, he wonders, “I wonder why he picked Cambodia?”

“That probably is badder water than this,” Eliza says, bringing the boat back out towards the channel. “There are 190 Waterkeepers around the world, and we have a conference every year, so people come in from all over. The stories, as we grow more internationally . . . I mean, China? India? We think we’ve got problems here? They’re really bathing in raw sewage and nothing else. And the level of toxic pollution? India has all of these tanneries, and there are kids working them, kids are just dying.”

As recently as 10 years ago, it was common to see children and adults splashing into the water from the wooden piers jutting from Locust Point, something Eliza Steinmeier says she hasn’t seen in her more recent rounds of the harbor, a trend which could have as much to do with gentrification as environmental awareness.

In general, she would caution against diving in anywhere in the Patapsco; as the Steinmeiers set out this morning she cautioned Matt to wear gloves for his water-sampling duties. She says she’s seen people swimming in the Middle Branch, where the water is generally considered to be cleaner, but since she started the bacteria testing, she says she would probably pull the boat over and advise them to stop.

They are making the rounds of collection sites to gather water samples that will be tested for enterococci, bacteria believed to have a high correlation with sewage, more specifically, fecal matter. Enterococci are found in the systems of most healthy adults and a smaller percentage of children, according to a 1990 Clinical Microbiology Review article on the subject. Because they appear in high quantities in human waste, they are often used, as Steinmeier is using them today, to test for the presence of sewage.

She has been testing since April, at sites where the city’s storm-water system empties into the harbor. The city conducts its own tests for water quality just inside some of the dozens of storm drains that lead to the harbor; Steinmeier tries to cover some of the others.

Today, the little boat will visit 10 sites, next week she’ll head over to the Middle Branch to test there, then back to this side the week after that. The samples are good for about six hours before she needs to get them to a lab.

What she’s found so far is troubling: Especially after a rainfall, the levels of bacteria regularly exceed levels the state sets for infrequent human contact. Steinmeier hopes to make the complete data available to the public soon, through the Waterkeeper web site (baltimorewaterkeeper.org), along with the city’s data.

As she explains this, a gull swoops down to a patch of roiling water and makes off with a small silver fish. It is likely a menhaden, a filter fish that spawns in the Atlantic and makes its way into the coastal waters. They are plentiful in the Chesapeake Bay, though fished commercially for oil and meal, and they form an important link between the algae they eat and the larger fish that prey on them. When a school of menhaden is attacked, they try to escape near the surface, jumping in large numbers. The cumulative effect sounds like rain.

It’s something Jack Cover, the general curator at the National Aquarium, sees from his office window all the time. “I’ll look out and you can see these events happen out there. Most people wouldn’t believe [they] were happening in the Inner Harbor,” he says. “You’ll see suddenly these big flocks of seagulls sort of circling around and diving. What’s happening there is that bigger predatory fish, like striped bass, are circling around a school of menhaden, and driving them to the surface. The seabirds are just diving–boom, boom, boom–to get these smaller fishes. You see these big schools of striped bass come in. It’s surprising the things you’ll find.”

In addition to the menhaden, the harbor contains white perch, bay anchovy, gizzard shad, Atlantic croaker, striped bass, and brown bullheads, all of which died off in substantial numbers and were counted by the Department of Natural Resources in a fish kill last spring. Steinmeier says she spots fish mostly when the oxygen content of the harbor is low, as during the recent fish kill. They will come up toward the surface of the water, gulping for air. Occasionally, an American eel will rise from the depths; crabs gather along the piers and seawalls. Cover says the ducks that come to the harbor to eat algae lining the sea wall at low tide will take refuge in the plant pots around the promenade, hiding in plain sight as tourists walk by unaware.

Cover is standing in front of a series of photographs at the aquarium, explaining how things are supposed to work in the Eastern forests of the United States, which is not generally how they work now.

“A lot of leaves fall off of deciduous trees, and you get this big organic banquet–a lot of nutrient loading,” he begins. “But when that happens, the forest is a sponge holding the rain water.” The trees and other plants of forested land filter and absorb most of the nutrients (largely nitrogen) from the water before it eventually trickles into creeks, then rivers, then the bay.

“When you replace that [forest] with all these hard surfaces . . . anybody who’s developing an area, they want to get the water away as quick as they can when there’s a storm event,” Cover continues. “That’s the exact opposite of what nature would do, where it would be percolating through, being absorbed.” As a result, water burdened with nutrients and sediment that would ordinarily be filtered out flows across the pavements and through the storm sewers of metropolitan Baltimore and drains directly into the bay.

The problem of nutrients in the water due to runoff is, in some ways, a thornier problem for the harbor than the sewage Steinmeier is detecting. There is, ultimately, only one solution for the sewage, and it requires the city to replace and fix its aging infrastructure, a project that, while expensive and time-consuming, is underway thanks to a federal mandate. Nutrients flushed through the Jones Falls and other tributaries require a different kind of public will. Cover points to things like green roofs, or the planting boxes filled with native grasses outside the aquarium, both of which help fill the role of the vanished forests and marshes–to hold the rainwater and extract nutrients before the fresh waters flowing down from the Piedmont plain begin to mix with the salt water from the Atlantic in the Chesapeake.

As Jim Peters steps through the marsh, something flashes across the path.

“Did you see that muskrat?” he asks, pointing out a patch of the path where something has been working to undermine it.

This small wetland preserve, bordered on one side by the Port of Baltimore and the other by Fort McHenry, is a testament to what Cover calls “the resilience of nature,” and Peters knows it well. The retired science teacher has been watching it for 10 years, cataloging the wildlife he sees here, and trying to help it along.

“I’ve had river otter on two occasions within the last three years,” he says. “Right now I’ve got a buck who’s in the velvet stage–his antlers are just forming. They swim across the Middle Branch from where they have better habitat on the other side. I’ve seen as many as six does grazing here in the early morning before the maintenance people come to work. I’ve had raccoons, I’ve had possum, cottontail rabbit, we’ve got squirrel of course, occasionally a feral cat. I’ve had a family of red foxes over the past 10 years. The female had a den here and raised kits. The old female got very tame and accustomed to me, and would often follow me while I was monitoring, staying 20 or 30 feet back, and when I would stop she would sit down, like a dog, and watch what I was doing. She died last year, I think of old age. The new female is so skittish. If we see her at all it’ll be like a bolt of lightning.”

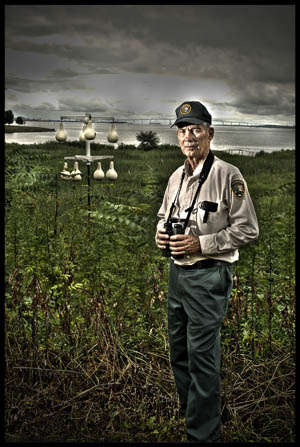

Since coming here in 1999, Peters has counted 253 species of birds in this little patch of land, a tally made all the more remarkable because the marsh is manmade–built over the tunnel finished in mid-’80s to carry Interstate 95 under the Baltimore Harbor.

In 1997, the land was taken over by the National Aquarium, which was looking for a field station for research, and when Peters came here, his first task was to sit in a lawn chair with a pair of binoculars and write down what he saw. The trails weren’t here then; he would walk out across the rip rap. Sometimes, he lost track of time, and the tide would come in, forcing him to wade back across. Now he comes down three days a week or so, leading tours from September to May when the bugs aren’t as bad.

The project started as an experiment in getting rid of phragmites– a swamp grass native to North America, but not on the East Coast–an invasive species, likely carried here in European ships at the beginning of the 20th century, used as packing material to transport goods. Capable of sending out shoots 30 to 40 feet long, with nodes every six inches that can sprout a new plant, the dense phragmites provide little shelter for wildlife, and threatens the native spartina grasses. Here in the marsh, where birds circle the small fish hiding in the tall grass, it is easy to see the connections between species that form the fragile ecosystem.

Baltimoreans have been upsetting that balance in one way or another almost as long as there have been European settlers here. In fact, the black muck at the bottom of the harbor presented one of the first civic challenges to the City of Baltimore. Ships could unload at the deeper water of Fells Point, but the water off Jonestown, at the basin in front of Federal Hill, ran down into a stinking mud flat. In the 1780s, the basin was dredged by elaborate “mud machines” consisting of barges and scoops, powered by horses walking inside a gerbil-wheel contraption. In the early part of the 19th century, steam dredges were employed. Today, although commercial shipping traffic seldom comes any further than the docks at Domino’s sugar, the basin at the northwest end of the channel is as deep as 30 feet.

The harbor is affected by the tides–rising and falling as much as one foot over the course of a day, and there are three currents in the deep channel. The bottom current, consisting of denser salt water, flows inward. The top current, weaker and affected greatly by the wind, also flows inward from the mouth of the Harbor. The middle current brings a mixture of the two outward. The relative calm of the Harbor makes it a sediment trap–the bottom layers of the Chesapeake Bay, stirred by waves and suspended in the water, flow inward at a greater rate than the limited outward current can carry them away, resulting in the need for a constant schedule of dredging to keep the shipping lanes open, and the depth of the channel has increased with time and the size of ships. The channel leading to Fort McHenry from the bay proper, 17 feet in 1830, is now dredged to 50 feet, and the bottom sediment collected by the dredges is considered contaminated and contained at Hart-Miller Island outside the Key Bridge.

During the most recent dredging of the area around Fort McHenry in 2003, workers turned up some 5,000 cubic yards of sediment, which was loaded into barges and transported to Hart-Miller, where it was sifted through a giant screen called “the Grizzly.” The dirt and clay were washed through the screen, leaving behind rocks, tire, cables, scrap metal, and a large number of unexploded bombs, necessitating the assistance of a bomb squad.

A report from the Army Corps of Engineers lists the ordnance recovered: more than 1,000 20mm casings, cartridges, and projectiles; smaller numbers of projectiles ranging from 37-175 mm and from 3 to 5 inches; a 3.5-inch rocket; a Soviet hand grenade; and seven double barrel .22 caliber pistols. They also recovered 46 historic weapons, from a 1-inch grape shot to a 320-pound Rodman mortar–a type used during the Civil War. A number of projectiles probably dating from the 1814 battle of Fort McHenry were found, some of which have been preserved by the National Park Service there.

The dredging process is not a delicate one. Details about where exactly things were found, were not kept as barges moved from one area to another. More fragile items didn’t make it. Susan Langley, who is Maryland’s underwater archaeologist, was called in to consult on the artifacts that survived.

“Not surprisingly,” she says, “when I asked them, they said, ‘We never find glass or ceramics.’ Just these big metal things that clog up the grizzly.”

The rusting hulk of the Governor Robert M. McLane, the flagship of Maryland’s oyster police force that patrolled for poachers from 1884 until 1948, occupies a shallow patch adjacent to the Museum of Industry on Key Highway, but Langley says it is unlikely that there are any shipwrecks in the Baltimore Harbor, and the McLane was more abandoned than wrecked. Wrecks have been found elsewhere in the bay, but she has to be cagey about the locations, so as not to attract treasure hunters. The current shipping channels into Baltimore follow the historic ones, and have been dredged for centuries. Modern detritus along the bottom makes it difficult to scan for artifacts, so the dredging operations are the best chance to uncover anything.

David Tebera, the diver, is waiting for a part he’s ordered for his underwater camera to come in, then he says he’ll go looking for a Playstation Portable that was dropped in the water. Like Langley, he’s reluctant to reveal the location of his underwater bounty. He’s aware that the game will likely be useless after its swim, but he says the owner is hoping to recover the memory card. It’s something to look for, anyway, an excuse to go back in the water.

“Some people do crossword puzzles,” he says. “This is my puzzle. What I love about the harbor is that everyone else is on land, but I’ve got one foot in the water. This is my world.”

This story originally appeared Jul. 29, 2009 in the Baltimore Citypaper